In the previous post in this series, we explained that WPE is a WebKit port optimized for embedded devices. In this post, we’ll dive into a more technical overview of the different components of WPE, WebKit, and how they all fit together. If you’re still wondering what a web engine is or how WPE came to be, we recommend you to go back to the first post in the series and then come back here.

WebKit architecture in a nutshell

To understand what makes WPE special, we first need to have a basic understanding of the architecture of WebKit itself, and how it ties together a given architecture/platform and a user-facing web browser.

WebKit, the engine, is split into different components that encapsulate its different parts. At the heart of it is WebCore. As the name suggests, this contains the core features of the engine (rendering, layout, platform access, HTML and DOM support, the graphics layer, etc). However, some of these ultimately depend heavily on the OS and underlying software platform in order to function. For example: how do we actually do any I/O on different platforms? How do we render onscreen? What’s the underlying multimedia platform and how does it decode media and play it?

WebCore handles the multitude of potential answers to these questions by abstracting the implementation of each component and allowing port developers to fill the gaps for each supported platforms. For example, for rendering on Mac, Cocoa APIs implement the graphics APIs needed. On Linux, this can be done through different implementations via Wayland, Vulkan, etc. For networking I/O on Mac, the networking APIs in the Foundation framework are used. On Linux, libsoup fills that gap, and so on.

On the opposite side, for browser implementors to be able to write a browser using WebKit, an API is needed. WebKit, after all, is a library. WebKit ports, besides providing the platform support described above, also provide APIs that suit the target environments: The Apple ports provide Objective-C APIs (which are then used to write Safari and the iOS browsers, for instance), while the GTK+ port provides a GObject-based APIs for Linux (that are used in Epiphany, the GNOME browser, and other GNOME applications that rely on WebKit to render HTML). All of these APIs are built on top of an internal, middle-man, C API that is meant to make it easy for each port to provide a high-level API for browser developers.

With all this in place, it would seem that it shouldn’t be so difficult for any vendor trying to reuse WebKit in a new platform to support new hardware and implement a browser, right? All that you need to do is:

- Implement backends that integrate with your hardware platform: for multimedia, IO, OS support, networking, graphics, etc.

- Write an API that you can use to plug the engine into your browser.

- Maintain the changes needed off-tree, that is, outside the source code tree of WebKit.

- Keep your implementation up-to-date with the many changes that happen in the WebKit codebase on a daily basis, so that you can update WebKit regularly and take advantage of the many bug fixes, improvements, and new features that land on WebKit continuously.

Does that sound easy? No, it’s not easy at all! In fact, implementation of ports in this fashion is strongly discouraged and vendors who have tried this approach in the past have had to do a huge effort just to play catch-up with the fast-paced development of WebKit. This is where WPE comes to the rescue.

Simplifying browsers development in the diverse embedded world

To simplify the task of porting WebKit to different platforms, Igalia started working on a platform-agnostic, Linux-based, and full-featured port of WebKit. This port relies on existing and mature platform backends for everything that can be easily reused across platforms: multimedia, networking, and I/O, which are already present in-tree and are used by Linux ports, like the GTK one. For the areas that are most likely to require hardware-specific support (that is, graphics and input), WPE abstracts the implementation so that it can be more easily provided out of tree, allowing implementors to avoid having to deal with the WebKit internals more than what’s strictly needed.

Additionally, WPE provides a high-level API that can be used to implement actual browsers. This API is very similar to the WebKitGTK API, making it easy for developers already familiar with the latter to start working with WPE. The cog library also serves as a wrapper around WPE to make it easier still. Once WPE was mature enough, it was accepted by Apple as an official WebKit port, meaning that the port lives now in-tree and takes immediate advantage of the many improvements that land on the WebKit repository on a daily basis.

How does WPE integrate with WebKit?

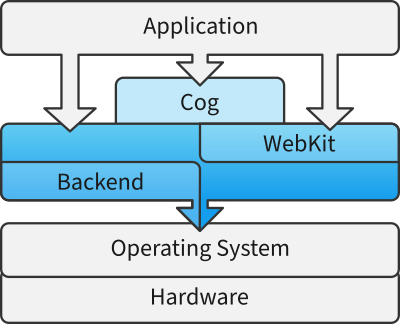

The WPE port has several components. Some are in-tree (that is, are a part of WebKit itself), while others are out-of-tree. Let’s examine those components and how they relate to each other, from top to bottom:

- The Cog library. While not an integral part of WPE, libcog is a shell library that simplifies the task of writing a WPE browser from the scratch, by providing common functionality and helper APIs. This component also includes the cog browser, a simple WPE browser built on top of libcog that can be used as a reference or a starting point for the development of a new browser for a specific use case.

- The WPE WebKit API: the entry point for browser developers to the WebKit engine, provides a comprehensive GObject/C API. The cog library uses this API extensively and we recommend relying on it, but for more specific needs and more fine-tuning of the engine, working directly with the WebKit API can be often necessary. The API is stable and easy to use, especially, and for those familiar with the GTK/GNOME platform.

- WPE’s WebCore implementation: This part, internal to WebKit, implements an abstraction of the graphics and input layers of WebKit. This implementation relies on the libwpe library to provide the functionality required in an abstract way. Thanks to the architecture of WPE, implementors don’t need to bother with the complexities of WebCore and WebKit internals.

- The libwpe library. This is an out-of-tree library that provides the API required by the WPE port in a generic way to implement the graphical and input backends. Specific functionality for a concrete platform is not provided, but the library relies on the existence of a backend implementation, as is described next.

- Finally, a WPE backend implementation. This is where all the platform-specific code lives. Backends are loadable modules that can be chosen depending on the underlying hardware. These should provide access to graphics and input depending on the specific architecture, platform, and operating system requirements. As a reference, WPEBackend-fdo is a freedesktop.org-based backend, which uses Wayland and freekdesktop.org technologies, and is supported for several architectures, including NXP and Broadcom chipsets, like the Raspberry Pi, and also regular PC architectures, easing testing and development.

An implementor interested in building a browser in a new architecture only needs to focus on the development of the last component – a WPE backend. Having a backend, starting the development of a WebKit-powered browser is already much easier than it ever was!

For a more detailed description of the architecture of WPE and WebKit, check this article on the architecture of WPE.

OK, sounds interesting, how do I get my hands dirty?

If you have made it this far, you should give WPE a try!

We have listed several on the exploring WPE page. From there, you will see that depending on how interested you are in the project, your background, and what you’d like to do with it, there are different ways!

It can be as easy as installing WPE directly from the most popular Linux distributions. If you want to build WPE yourself, you can use Yocto and if you’d like to contribute—that’s very welcome!

Happy hacking!

Claudio is long-time WebKit contributor from Igalia, working in different areas of WebKit, WPE, and the stack around it.